One pre flight item that is typically overlooked, brushed off or (sometimes) not taught at all is the Departure and Emergency Actions Briefing or the Pre Takeoff Briefing.

Not to be confused with a “SAFETY” briefing that should be performed just before starting the engine, the departure briefing is typically made after the ‘run up’, before moving out of the run up area and approaching the hold-short line.

The goal of a departure and emergency actions briefing is to quickly declare the planned runway used for takeoff, course of flight and altitude(s) expected. Then a quick overview of what could go wrong on take off and what actions will be taken.

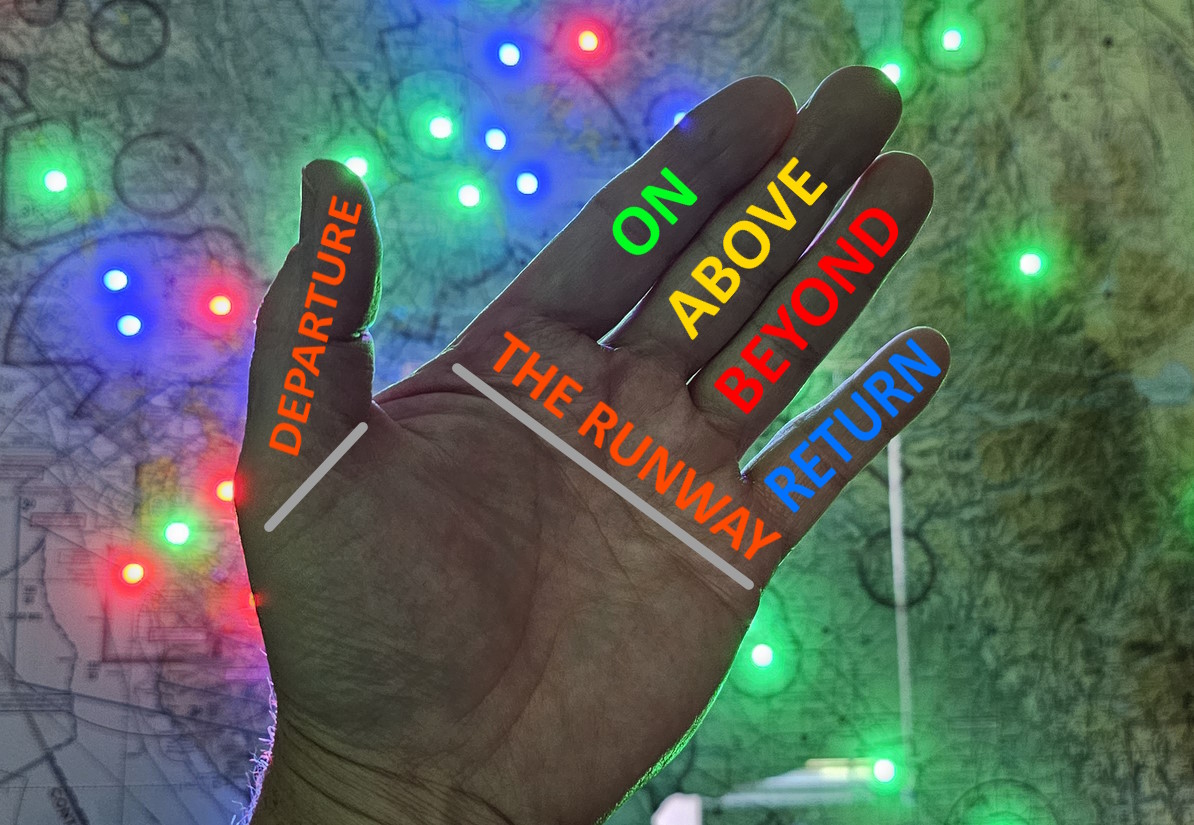

Departure and emergency action briefings can and should be specific to the airplane, the airport (naturally), the pilot’s capabilities and the flight being performed that day. The basic format is to have a plan for something going wrong at typically three important points during takeoff – the takeoff roll, immediately after getting airborne, and airborne but with no runway left to land on. Then the fourth item talks about the “Improbable Turn” back to the runway which, for those who have not practiced it, should not be performed at low altitudes and could simply be wrapped up by saying, “I will not attempt a return to the runway until I have at least 1,000 feet of altitude.”

There should be an expectation by every pilot each and every flight of aborting the takeoff and staying on the ground where it is far safer than flying with a problem. If something doesn’t look right, sound right or feel right, the goal should be to stay on the ground.

For example; a simple VFR departure briefing could be summarized as such, “We will be departing runway two seven with a downwind departure to the East climbing to seven thousand, five hundred.”

Quick. Easy. Simple. Everybody knows what runway we’re using (important for situational awareness especially at airports having runways with common departure points), how we’re leaving the terminal environment and what our planned or initial altitude will be.

It should then continue into the four parts of the emergency actions briefing with items one and two essentially the same every time, while three and four should be dynamic and specific to the airplane, airport (and runway configuration) and pilot’s ability/proficiency.

If I’m departing runway 27 at KCXP in daytime VFR conditions, my emergency actions briefing will sound something like this, “When we have an engine failure or any abnormality during the takeoff roll we will immediately pull the throttle to idle, apply brakes, avoid obstacles and taxi off if we can. When we have an engine failure or any abnormality immediately after takeoff we will land on the remaining runway, avoid obstacles, apply brakes and taxi off if we can. When we have an engine failure after takeoff with no remaining runway, we will bring the throttle to idle, mixture OFF, magnetos OFF, add flaps as needed, master switch OFF, cabin door UNLATCHED and perform a soft-field landing within 30° of centerline. Lastly, I would not attempt a return the runway unless I had “

Please note I’m using the word “when“, not “if” in these briefings. Flying long enough will invoke the law of averages and something will eventually happen where this plan will be put into action.

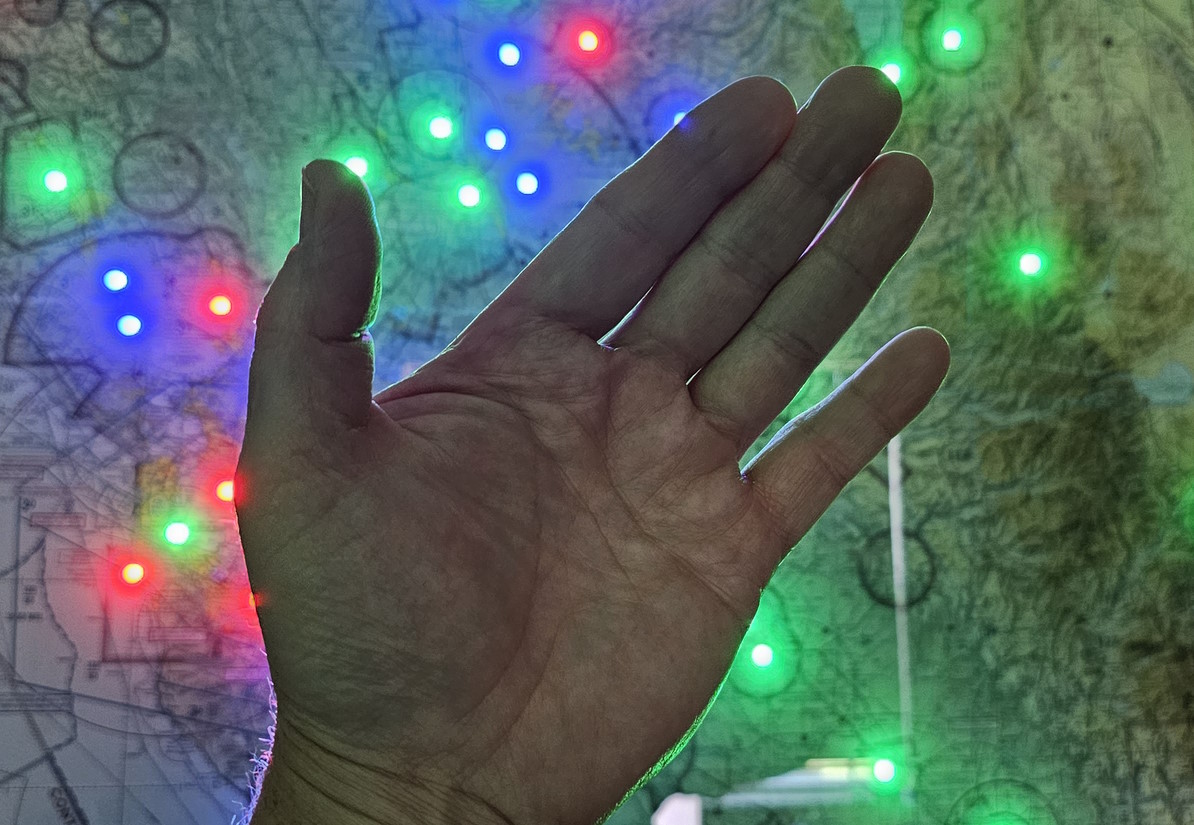

It may sound like a lot to say, but it really isn’t and is more of a practical conversation of planned actions and I’ve adopted a new and easy (for me!) method of remembering all the items needed for these briefings. My left hand!

Another briefing example which I typically use when flying out of KMEV in Minden, Nevada from runway 34 can go as such;

“We will be departing runway three four with a downwind departure to the South climbing to eight thousand. When we have an engine failure or any abnormality during the takeoff roll we will immediately pull the throttle to idle, apply brakes, avoid obstacles and taxi off if we can. When we have an engine failure or any abnormality immediately after takeoff we will land on the remaining runway, avoid obstacles, apply brakes and taxi off if we can. When we have an engine failure after takeoff with no remaining runway, we will bring the throttle to idle, mixture OFF, magnetos OFF, flaps as needed, master switch OFF, cabin door UNLATCHED and perform a soft-field landing within 30° of centerline since we have empty fields to the North. When we have an engine failure and at least 400 feet of altitude we will immediately unload the wings, turn left with 45° of bank to land on runway one two and announce our intentions to other traffic in the area.”

If you have more than one runway available, especially if they are not parallel, they should be considered for use in an emergency return – altitude and pilot ability permitting of course.

Looking at the wording of the briefing and imagining the actions of each possibility, it should make logical sense and be easily recited with very little practice (especially when looking at your left hand!). It’s not meant to be a perfect script, it is meant to be a quick talk about common sense actions that will likely need to be taken, set expectations for the departure and get everyone in the correct mindset. This way when something does happen we simply do what was briefed a minute ago.

If there are potential landing areas beyond the airport environment they should be included in the briefing. For example, “…If no runway remains for landing, we will bring the throttle to idle, add flaps as needed, mixture OFF, magnetos OFF, master switch OFF, cabin door UNLATCHED and perform a soft-field landing in the vacant lot to the right of centerline just past the runway…” or in a congested area, “…perform a soft-field landing on the highway in the direction of traffic avoiding the apartment complexes.”

All of this would not be complete without mentioning the “Impossible Turn“. The so-called “Impossible Turn” or “Improbable Turn” is something that can be used under certain situations and depends heavily on the wind/weather, the airplane’s current altitude, the pilot’s response time to the emergencyand the pilot’s proficiency, experience and familiarity with the airplane being flown. This is something that should be practiced at altitude, with about a five second ‘startle response’ time factor included because it involves more that just a 180° turn, which would only just parallel the departed runway, and warrants a more detailed discussion in another post.

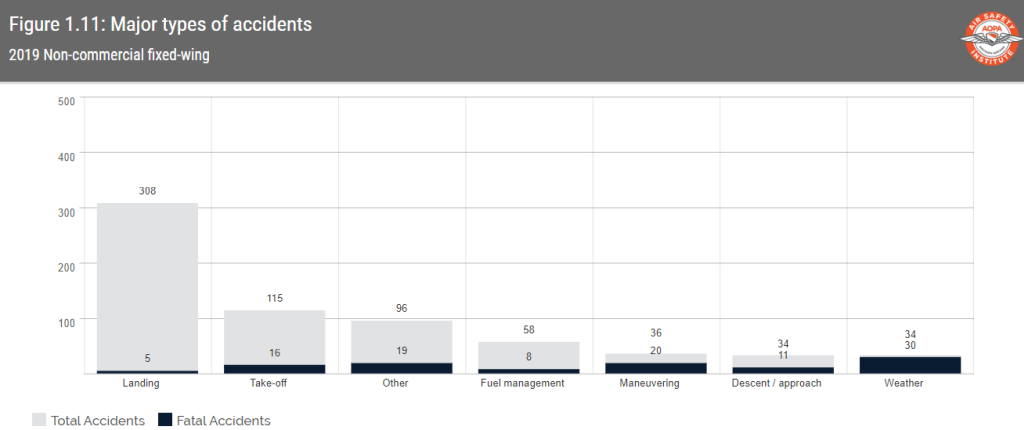

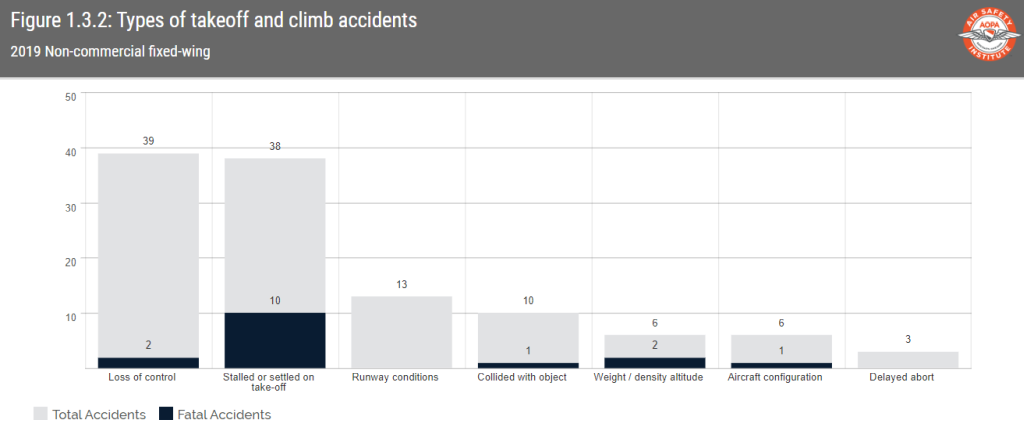

Remember that many GA pilots die in the traffic pattern with the most dangerous part of the pattern not the base-to-final turn (a.k.a. Graveyard Corner), but rather the takeoff and climb phase of flight which, year over year, tends to be two to three times more deadly even though far more people crash on landing. A comprehensive Joseph T. Nall Report for 2019 (the most current at this time) can be found here.

Prior reports can be found here on the AOPA website here.

Having a plan before takeoff is very important and can help prevent becoming part of an NTSB report and a statistic in future accident graphs.